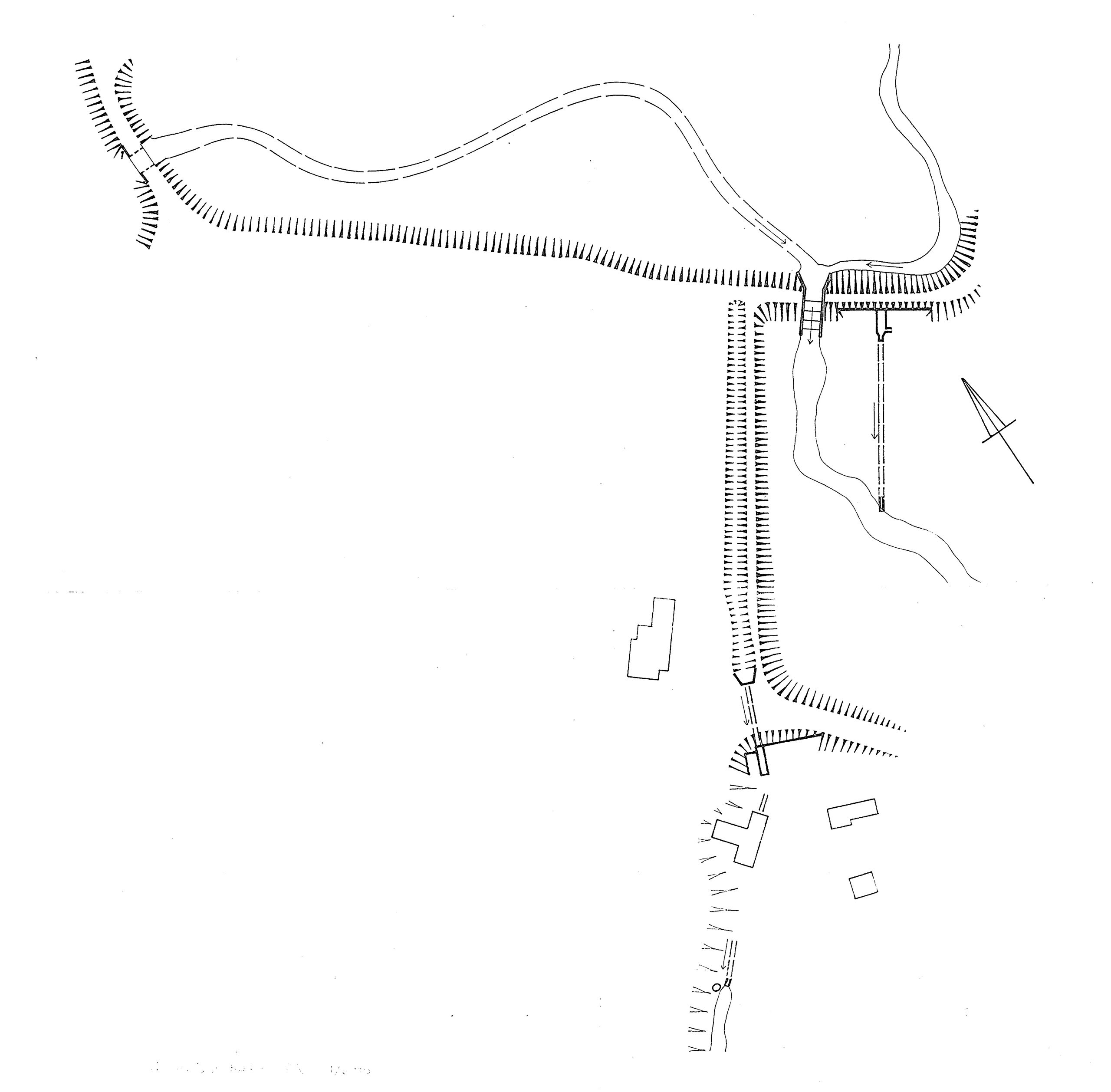

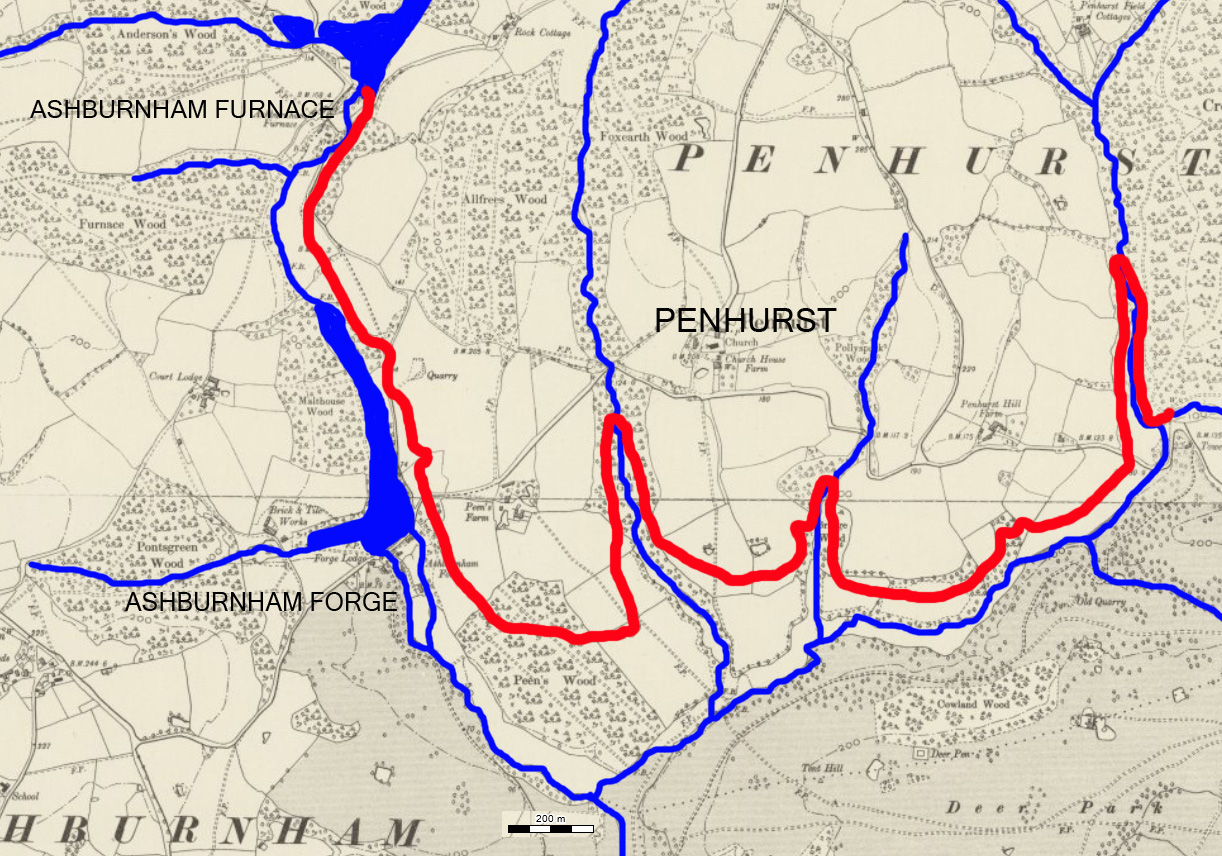

Ashburnham Furnace was the last furnace to cast iron in the Weald, being ‘blown out’ finally in early 1813. The layout of its site is more complex than for most furnaces in the region and more survives in the form of watercourses and residual wheelpits than on most others. In the mid 1970s David Crossley undertook a survey of these features of the site, resulting in this plan.

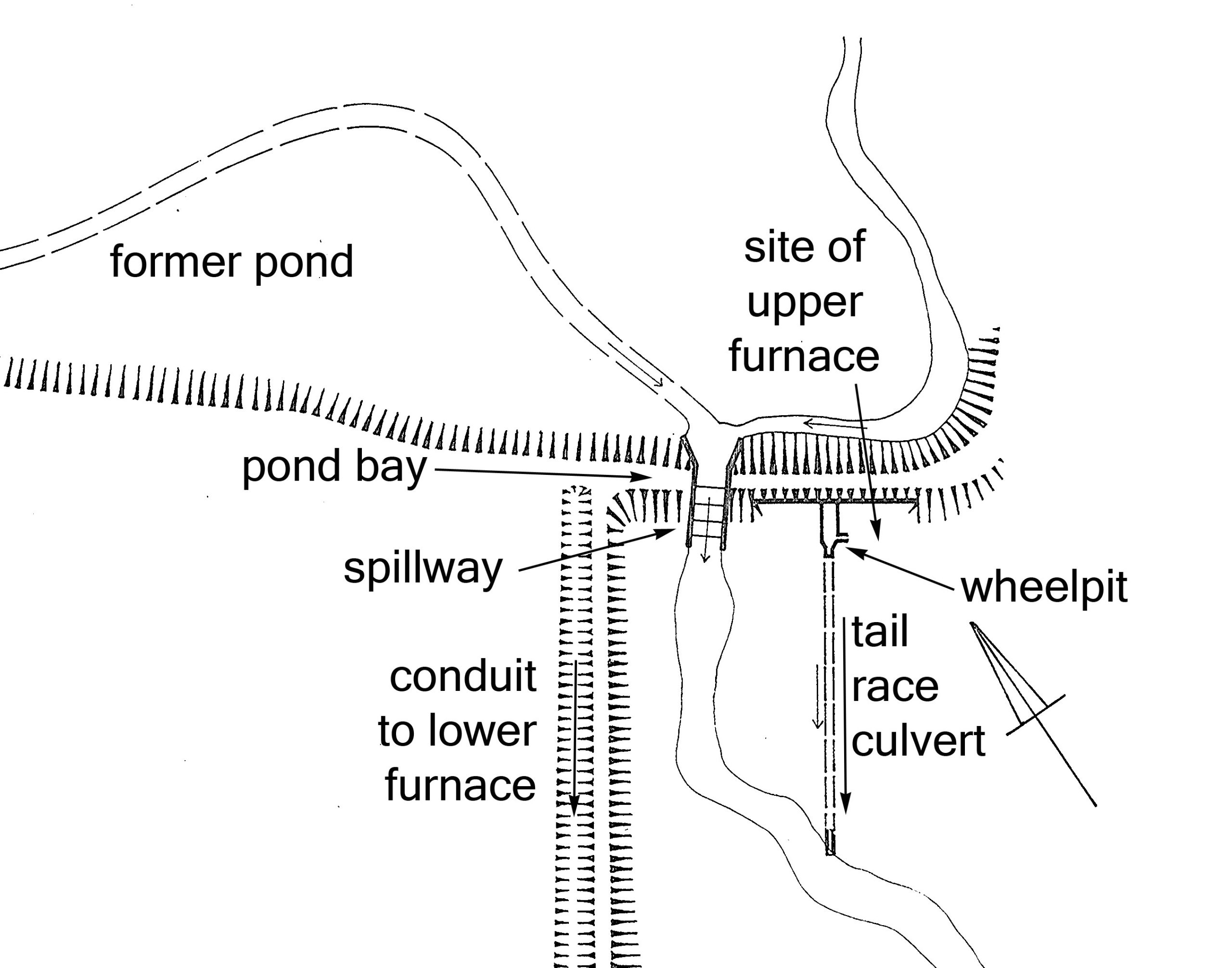

At most furnaces a single bay, or dam, was constructed across a valley to pen water to form a pond. On the downstream side a furnace was erected with a channel leading from the pond to an adjacent wheelpit for a waterwheel to power bellows. A spillway diverted surplus water from the pond when the furnace was not in use or during excessively rainy weather. Ashburnham had all of these and more.

In 1888, 75 years after the furnace closed, the Reverend R. F. Whistler, Rector of Penhurst, the parish in which part of the furnace site lay, wrote:

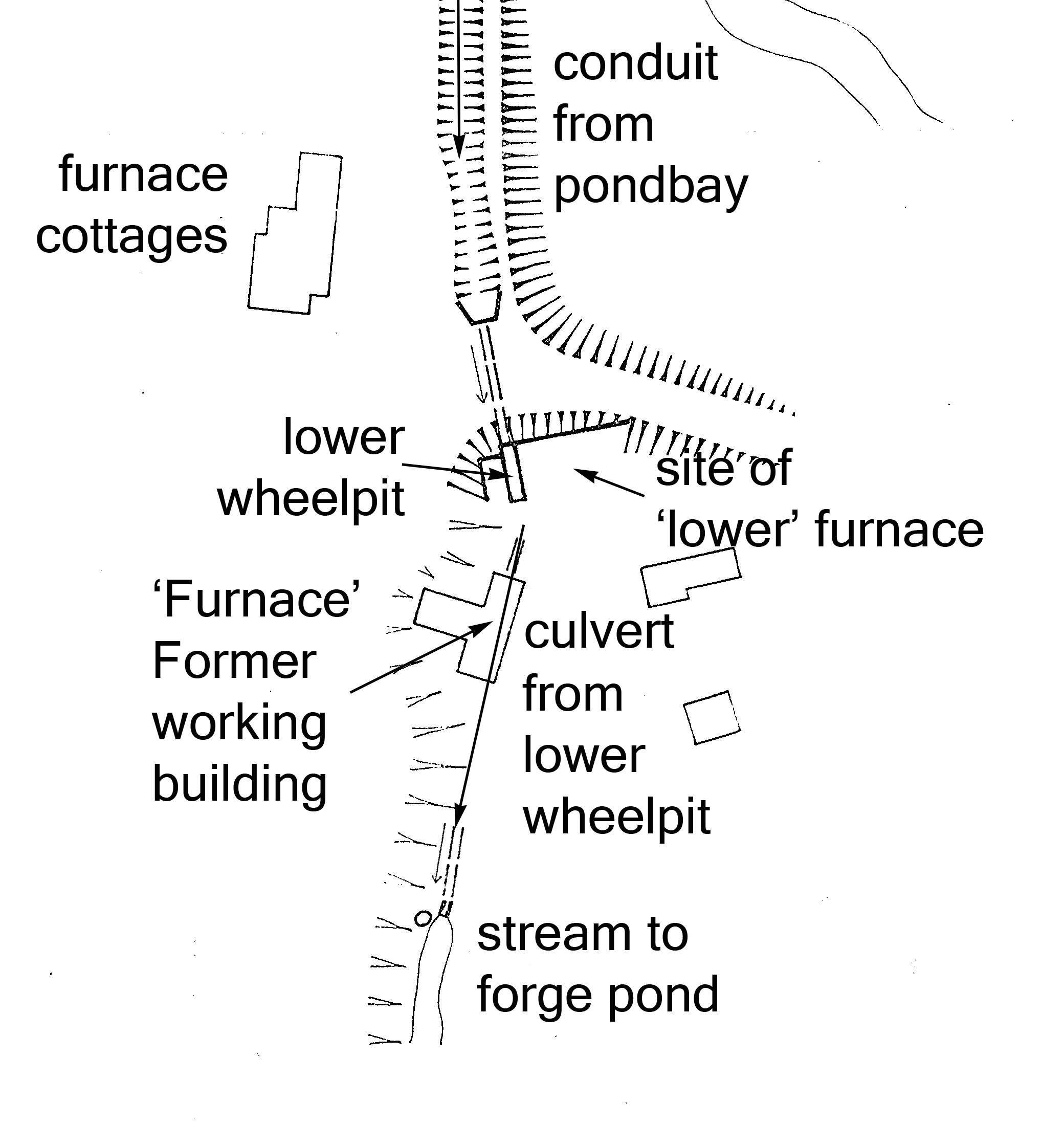

From the testimony of two or three other inhabitants, who though not engaged in the works had opportunities of observing them, we gather the following facts: When the works were abandoned there were two fires, a larger and a smaller; to serve these there were two pairs of bellows blown by means of wheels turned by water power, the current of which may still be seen. The lower furnace was much the larger, and there the ore (brought from the neighbouring woods) was smelted, and poured into moulds in which it was shaped into such form as might be required. Here were made fire backs, brand irons, and sometimes cannon and shot of various sizes; but, as a rule, the molten iron was shaped into pigs for general purposes. At the upper and smaller furnaces, near the present water gate, the guns were bored, and afterwards tested by the discharge of balls, many of which are still from time to time dug from the banks of the opposite wood in which they had been embedded.

The ‘two fires’ Whistler mentioned were located some 100m apart and necessitated a water-management system that could supply both from the same pond. The boring mill had been installed in 1766 to supplement an existing mill at Ashburnham Forge, further down the valley. Nothing remains of either furnace but David Crossley explored the area around the ‘upper’ furnace in 1976-7.

Probably the most dramatic feature of the site is the spillway, known locally as the ‘waterfall’, which formerly controlled the height of the water in the pond by means of stout boards that fitted into a pair of opposing vertical slots. When the furnaces were in operation the pond needed to be full, but the level could be lowered during the summer months; Wealden furnaces generally were in blast from about October to June. Two additional sluices through the bay allowed water to flow to the furnaces. How these were controlled is not clear, the control mechanisms not having survived.

All that survives of the ‘upper’ furnace is the wheel pit. Water was fed downwards into this through a brick-lined culvert intended to power a low-breastshot or undershot waterwheel whose rotating shaft would have operated the furnace bellows. The water from the pit was then culverted about 35m to the stream that crossed the site below the spillway. The culvert was necessary as the ground adjacent to the furnace would have been needed for access by wagons, horses and ironworkers. Subsequent to the closure of the furnace a cottage had existed on this site, known locally as Jimmy’s Garden, and the wheelpit was used as a cellar.

The water for the ‘lower’ furnace was carried from a sluice in the pondbay via an open conduit or leat along the western side of the site, parallel to the track past the furnace cottages, then culverted beneath the track to emerge above the lower wheelpit. The course of this channel, incidentally, aligns with the boundary between the parishes of Dallington and Penhurst. Again, the water descended steeply into the pit where it would have powered a low-breastshot or undershot wheel. A shaft would have run from the wheel to two bellows next to the furnace. The soil in this area is heavily charcoal-stained.

From the lower wheelpit the water was carried away through a culvert about 75m long that passed underneath the building, which is now the residence known as ‘Furnace’. This clearly indicates that the building was formerly a working part of the ironworks. It is not known if the culvert had been accessible from within the building but it is highly probable; why else build one over the other? There are two known inspection pits into the culvert: one immediately to the north of the building; and the other close to where the culvert emerges into the stream that flows down towards the forge pond. Near to this there is a pronounced mound where fragments of cannon mould can be picked up.

Apart from the house called ‘Furnace’ two other features of this site are worth mentioning. Firstly, the three furnace cottages, which comprise a contiguous building constructed during two different periods. The older part, to the north, two semi-detached dwellings, probably dates from the 16th century. To the south, Pay Cottage, so named because the ironworkers were paid through a window next to the front door, dates from the 18th century. It may well be that the Pay Cottage is contemporary with many of the surviving structures at the site, and that they date from the first decade of the 18th century when the ironworks were leased by the Forest Partnership from the Forest of Dean, or when the works were leased to Crowley & Co. in 1736. Both were substantial, wealthy ironmaking concerns.

The other feature is the leat, which was constructed to supplement the water in the furnace pond. It also was probably constructed in the first half of the 18th century, although no documentation is known to survive. Approximately 4.5km in length, it drew an additional flow from a tributary of the River Ashbourne near the site of the former Penhurst Furnace, which had operated in the 16th century but had long been abandoned. Originally about 1.3m deep, it largely follows the 30m contour and sections of it remain visible particularly in woodlands along its course.

© Wealden Iron Research Group 2025